Five Years of Scientific Discoveries with SLAC's LCLS

Since the success of its inaugural experiment five years ago, thousands of scientists have used SLAC's X-ray laser to probe previously unreachable extremes in fields ranging from biology to astrophysics.

Five years ago, on the eve of the first X-ray laser experiment at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Linda Young summed up her role in leading this inaugural exploration: "Wow ... Quite an honor, quite a responsibility."

Young, who studies interactions of light and matter at the scale of atoms and molecules, is director of the X-ray Science Division at Argonne National Laboratory. She chronicled her team’s pioneering experiment at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, in a series of blog posts in October 2009.

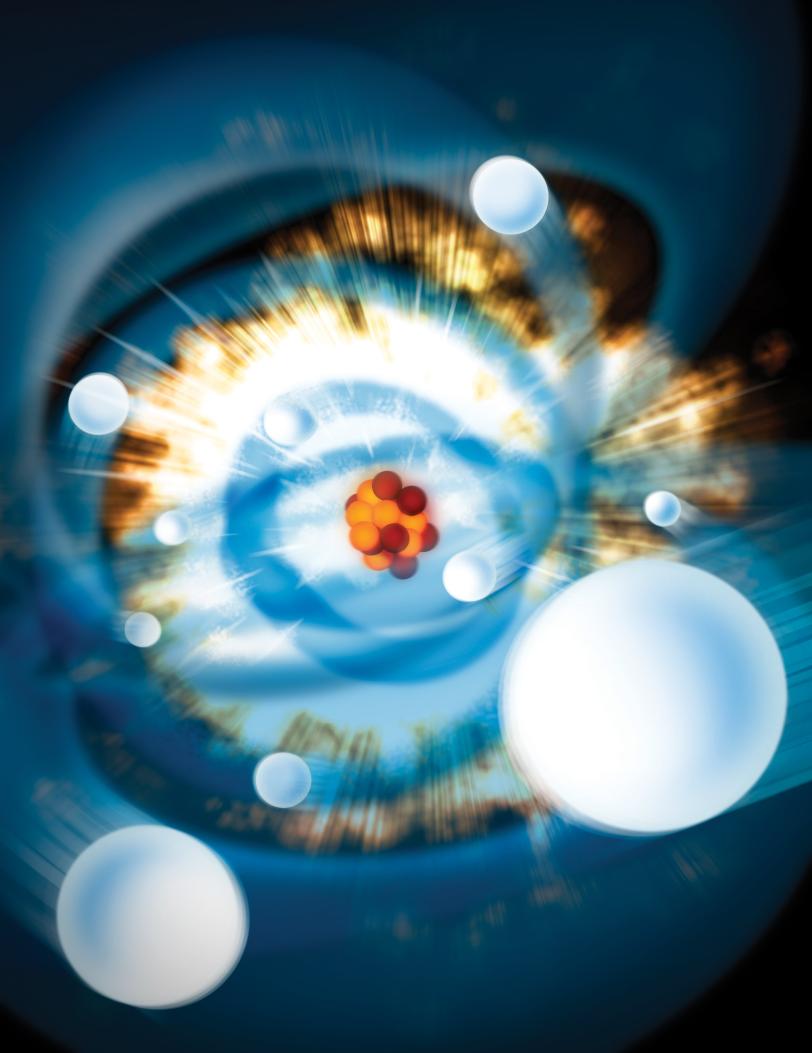

That first group of scientists studied what happens when intense X-ray pulses from LCLS, a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources used for research, hit neon atoms. The researchers learned how to precisely tune the pulses to peel away atoms' outer electrons or carve out their inner electrons, creating temporarily "hollow" atoms. This process had never been explored in such detail.

These and other results from early experiments provided a basic understanding of the extent and speed at which LCLS X-rays can damage or destroy samples – knowledge that is especially critical for producing accurate 3-D images of complex molecular structures.

"We've found out not only the basic processes that happen in atoms in response to LCLS pulses, but some of the subtleties that go along with it," Young said, reflecting on the progress made possible by experiments at LCLS.

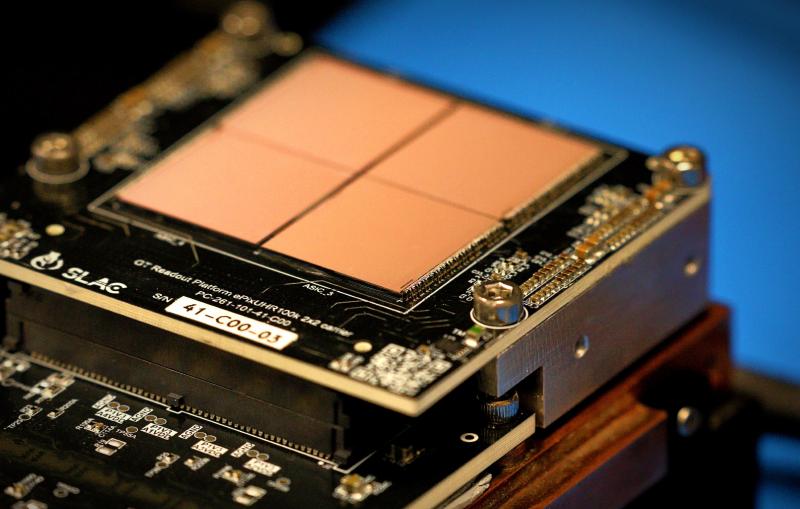

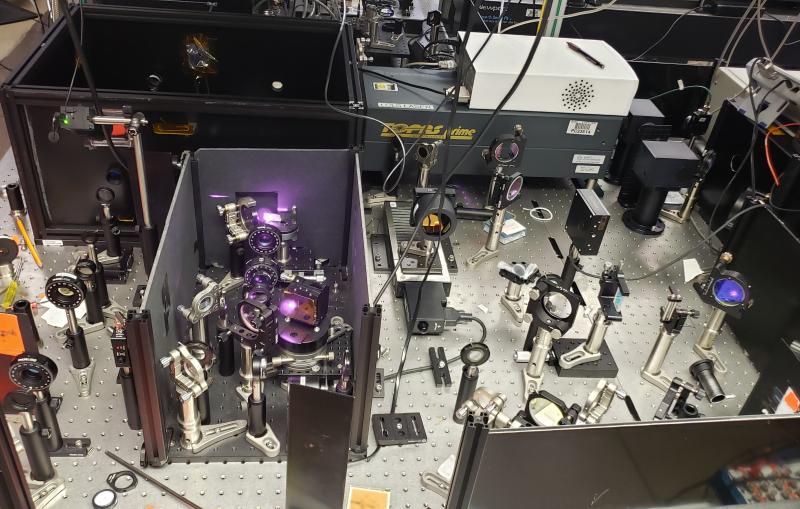

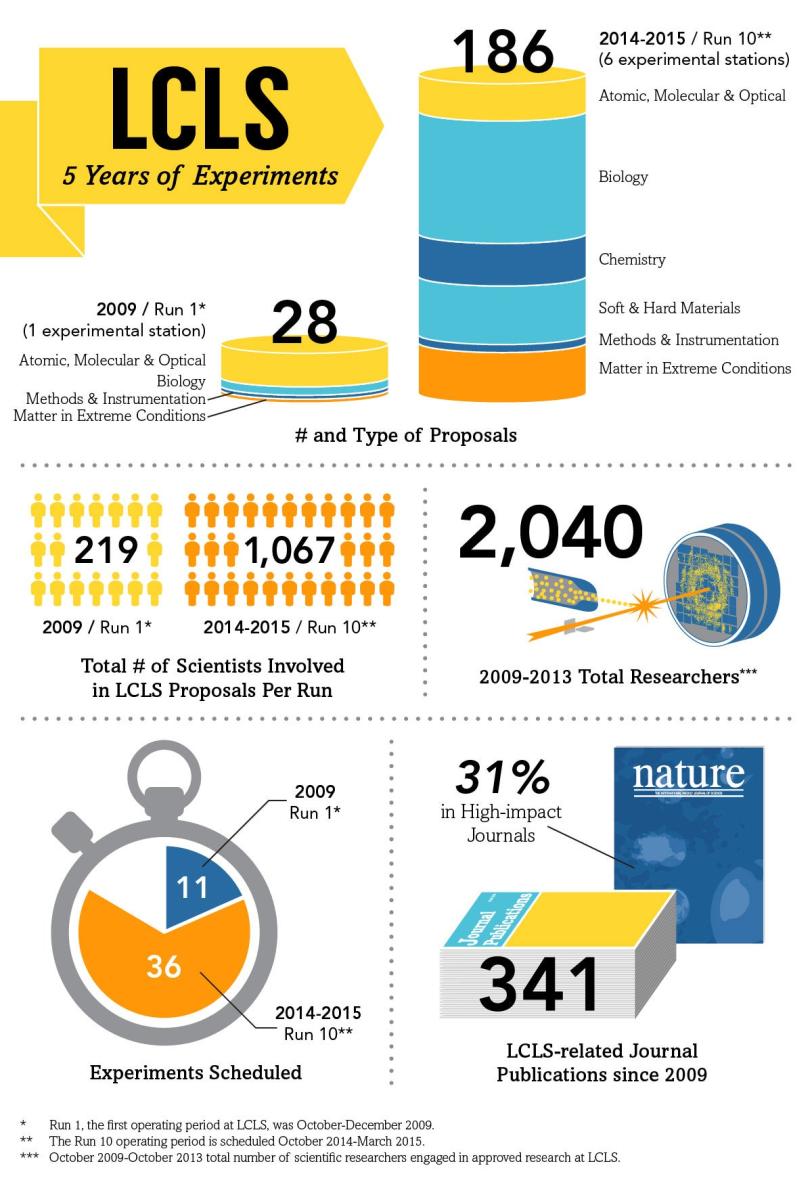

Since that first experiment, the number of LCLS experimental stations has multiplied from one to six, and thousands more scientists have probed previously unreachable realms in fields from biology and chemistry to materials science and astrophysics. LCLS experiments have generated hundreds of articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals, with almost one-third of them appearing in prominent journals like Science and Nature.

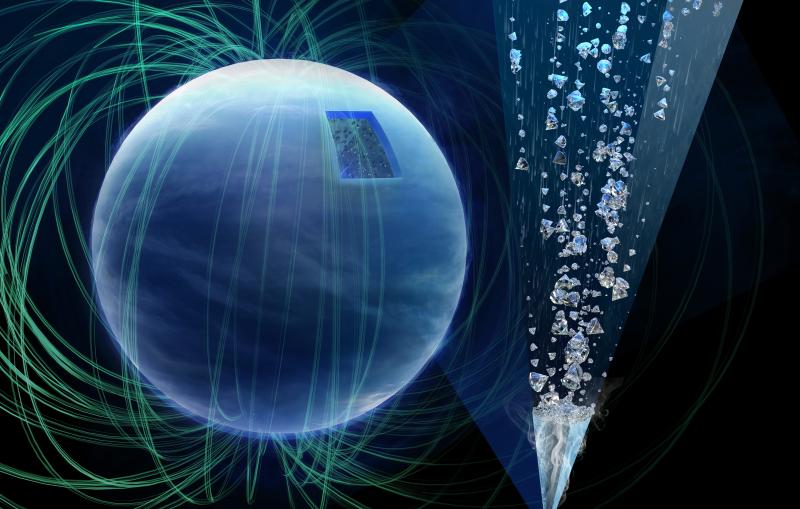

LCLS has already achieved important milestones in several fields, mapping the structure of an enzyme relevant to a disease called African sleeping sickness and a crystallized protein embedded in living bacterial cells, detailing quantum phenomena in microscopic droplets of helium, and learning how DNA guards against damage from ultraviolet light.

Young has returned to LCLS several times, most recently last spring. It seems there is always a steady supply of new instruments and techniques to try out at LCLS, she said: "The machine scientists keep coming up with new configurations that allow us to delve a little deeper."

Importantly, the sensitivity of the X-ray detectors has increased, she noted, and her team is now studying more complex molecules. Young said improvements in computer-based modeling should also help scientists prepare for LCLS experiments and interpret LCLS-generated data.

She added, "Science at LCLS is still rapidly evolving – I don't think it has lost its flavor of being very exploratory. We're just starting to scratch the surface."

The 2014 LCLS/SSRL Annual Users’ Meeting and Workshops event runs from Oct. 7-10 at SLAC.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.